I was sent to juvenile hall at 10 years old, and never once did I think about losing my voting rights or any other rights — besides my freedom.

While most kids were exploring the world, I was either being bounced around from one dysfunctional foster home to another or behind bars, having my formative years masked under the umbrella of shame and oppression the legal system imposes on children.

At 18, my mom told me to register to vote. When I got to the part about whether I was a Democrat or a Republican, I froze. “What am I?” I asked myself. I’m unsure what I checked, but it wasn’t Democrat or Republican.

By the time Election Day came around, I was again incarcerated and didn’t get the opportunity to vote.

The reality is that most of my adult life was spent in the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. I didn’t care about voting or laws that didn’t apply to me. My daily concerns were survival and coping with the harsh violence and deprivation of prison life.

My life, marked by early incarceration and systemic failures, has been a continuous struggle for recognition and rights. The act of voting is not merely a civic duty, but a personal triumph over a past that sought to silence me.

My views on voting and civil rights changed drastically in 2004 when Proposition 66 was on the California ballot. Prop. 66 was the first attempt to roll back the draconian three-strike law responsible for putting men and women behind bars for life, in some cases for trivial infractions. This initiative would have allowed me to get out of prison early if passed by voters.

I remember that election season encouraging our friends and family to vote for Prop. 66. We campaigned in the prison yard and passed out fliers with information about Prop. 66. I remember watching the election results on my tiny black-and-white television in my prison cell at Centinela State Prison. Prop. 66 led by a wide margin that evening as more votes poured in.

Sitting in my prison cell, I thought the proposition would win. But as the evening went on, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger appeared on my television screen, declaring that if Prop. 66 passed, California would release thousands of “rapists, murderers and child molesters.” When I saw this commercial, my heart and hopes diminished.

When the polls closed the following morning, the measure was defeated.

Since that somber day, I’ve always wondered if money, fame or votes mattered in that election.

Most people impacted by the criminal legal system take civil and voting rights for granted. We have witnessed time and time again how rights only apply to privileged people. A friend I met during my incarceration even voted for the three-strikes law.

He realized his mistake when he was sentenced under the law he supported.

It added over six years to the time he spent behind bars. He then understood how he and many California voters were misled into thinking the law only applied to repeat offenders. He also told me he believed laws are written for a select portion of society and did not think of himself as the part of society the three-strikes law targeted.

We laugh today when he tells me it was the first time he realized he did not belong to one of the privileged groups.

I was released early, not because of a change in law but because Gov. Jerry Brown saw the flaws in the California criminal legal system. My sentence was commuted at 48, which marked the end of a long and arduous journey. I missed many milestones, including the opportunity to exercise my right to vote — but that will change this year.

Registering to vote made me uneasy. I was now being asked to participate on a jury. I know as a “citizen” it is supposed to be my “duty” to vote. Nothing said this more to me than when I received a postcard from Assemblymember Juan Alanis asking me to help “eliminate early release for inmates” with my vote.

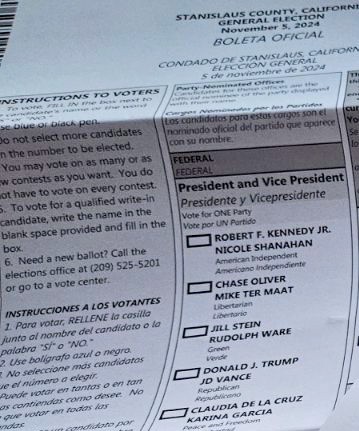

My ability to vote is even more relevant in 2024, given that it is my first opportunity to vote in a presidential election. The candidates, former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris are polarizing figures with solid support and opposition on both sides. I am somewhat disillusioned and question whether my vote will make a difference, though.

My skepticism stems from a lifetime of systemic neglect and my personal opinion that we have always lived in a divided country where rights don’t matter and laws are only applied to the underprivileged.

However, my internal struggle mirrors a broader societal question: Is voting worthwhile when the change we seek seems far-fetched? For me, voting is an act of empowerment, a symbolic gesture of resilience and determination.

Each vote I cast will be a step towards reclaiming my voice and identity and participating in a society I will always be somewhat excluded from. While doubts about the efficacy of voting persist, the importance of this right cannot be overstated.

It is through voting that I affirm my place in a democratic society and contribute to the collective voice seeking change.

Attributions: This article originally appeared in Cal Matter on September 11, 2024.

Photo Courtesy of Cal Matters