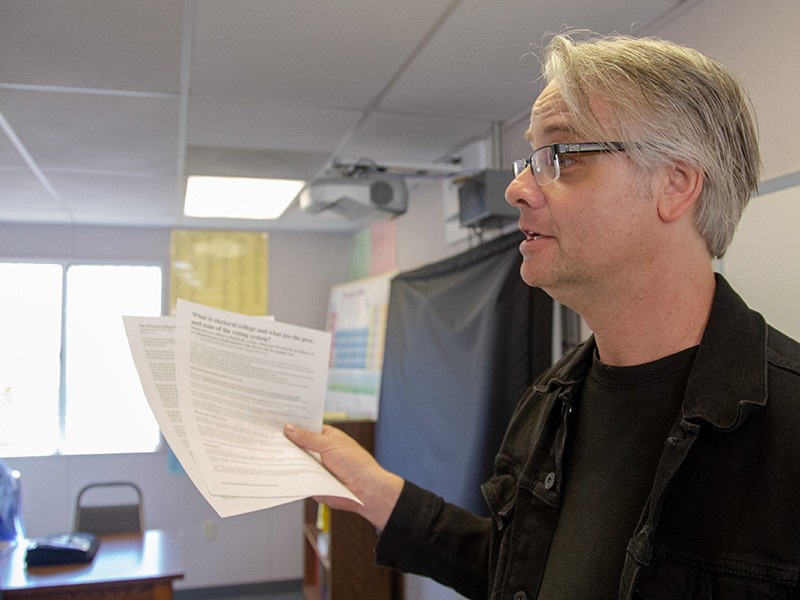

In February 2025, Mount Tamalpais College Communications Associate Bonaru Richardson, an MTC alumnus, had the opportunity to sit down with longtime faculty member Ian Sethre. Ian has taught history and political science at the college for eight years and helped organize a mock election at San Quentin during the 2024 presidential campaigns; he is also a Professor of History at the College of Marin. In this thoughtful conversation, Ian reflects on the unique dynamics of teaching inside a prison, the deep intellectual connections he has formed with students, and the broader implications of education within the carceral system.

What made you gravitate towards teaching at San Quentin?

Many years ago, I tutored in a GED program at Cook County Jail in Chicago. I was in college and out of my element because I’m from rural Colorado. Still, I recognized, even at that point, how education and access to education can empower people, or– it is a critical piece that gets overlooked– can also perpetuate division.

I know what you mean, but please give me an example.

For example, on the extreme, elites in this country often attend exclusive schools like Harvard, Yale, or Stanford because their parents did, and that perpetuates a class system and a degree of wealth and power. Of course this happens throughout the four-year system. And then you look at people on the other end of the economic spectrum who are held back by unequal access to resources and economic barriers. They might see an ad for a for-profit university on television promising they can become a nurse or web designer in two years if they just pay this much money–and then they end up in deeper debt. That’s predatory. It’s a cliche at this point to say that education empowers and provides opportunities. It can, but it doesn’t always work the way it should.

How does your teaching at San Quentin differ from the College of Marin?

Often, the students in San Quentin have self-actualized in ways that younger students on the outside haven’t quite yet. Generally speaking, they’re older and more experienced, so they’re more aware of their strengths and weaknesses. That level of motivation in the classroom in San Quentin translates into more consistent, reliable, and quality participation.

Have you had interactions with incarcerated students where they put up a brick wall?

As a teacher, you can’t let one person – and I still make this mistake; I’m preaching something that I have a hard time internalizing – you can’t let one person’s disposition shape the entire class dynamic. It’s a matter of making sure that all of the students maintain a culture of the classroom that’s empowering and collaborative, and also recognizing that, while this one person may be resistant or skeptical, on the whole, they probably want to be there. In that case, it’s a matter of time and persistence, and allowing those particular students to find their place and comfort level. And it’s a mistake for anybody to go in there and feel that just because they maybe have good intentions, they’re automatically going to be trusted by the people that they’re trying to reach.

What would you like to prioritize in your classroom?

Being able to relate to each other on an intellectual level. There is a socialization piece. I think that everybody in there feels that this educational enterprise is making them a better person.

The experience of being in the classroom, which has to be a deviation from the unpleasantries of so many of the other carceral settings in this state, hopefully, makes people feel that they have a more enriched existence.

You don’t just teach, you go outside of your realm of teaching and run extracurricular activity classes. What motivates you to do this?

I don’t mean to be trite about it, but I have discovered a real, genuine learning community in San Quentin. And that exists on a few different levels. The students themselves value that community and they perpetuate it. They’ve defined the culture of the place, and I like being around that energy. I respect their motivation, resilience, and dedication. So I guess a shorter answer would be to say I like to be a part of something larger and contribute what I can that may be of value to it.

I heard you play in a band.

Music has been an outlet for me for most of my life, and it’s another social opportunity to be part of something bigger, fun, and invigorating. I’m in two bands, actually, and we play at various bars around the Bay Area, usually about once a month with each. Soulbillies played a really fun show in the chapel at San Quentin about five years ago.

How do you see the future of education in the carceral system evolving?

For about a decade, there’s been increased popular consciousness about mass incarceration. There was the Ava DuVernay documentary, 13th, and several others, and Ear Hustle has done a lot to humanize incarcerated people. Unfortunately, the crisis of the COVID-19 outbreak drew a lot of attention to the prison system, especially here. Black Lives Matter and the awareness of police brutality. I do think that there’s more attention and expectations perhaps of change.

I’m hoping these reforms don’t stop with San Quentin, because it is treated like the crown jewel, when it should be a model for what these rehabilitation centers–if we’re going to use the term–are supposed to be.

Due to their circumstances, sometimes the people I’ve met inside seem to have done more soul-searching and coming to terms with who they are and who they want to be than a lot of people on the outside have.

I’m not even going to comment on that.

Well, I mean, maybe you don’t agree. I respect that.

Well, I’ve been incarcerated, so it’s going to be biased.

That’s another important point. I’m aware that I’m working with a very small segment of the incarcerated population who have self-selected out of the general population. I have to be careful about what I do when I’m outside of prison because there are a lot of ways that I feel like information gets misinterpreted. One is that some people want to hear horror stories. They expect to hear that prison is a scary, violent place. I’ve been asked if I wear a sidearm in the classroom. I’m also uncomfortable with the whole concept of altruism–the whole white savior complex and “isn’t it great what you’re doing?” because that’s simplistic and unhelpful.

I don’t like that either.

That’s something that we need to be very conscious of. The reality is that the system has been structured in such a way for so long that sometimes it’s white people of privilege who are in a position to do something, but there has to be a self-awareness that comes with that. And that’s a hard thing to teach.

There is a quote attributed to Nelson Mandela,

“…no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.”

That sentiment resonates. And the guys in there? All “People of California vs.” whoever, and we have an obligation to know what is being done in our name. And if this is about correction and rehabilitation, we should be involved in that, too.

Photo courtesy of R.J. Lozada